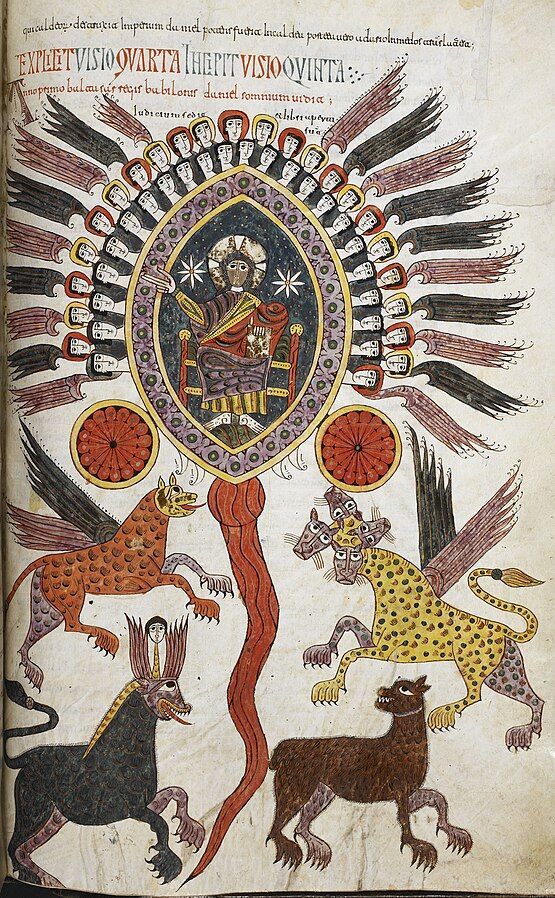

If you’ve not read Daniel 7 recently, I encourage you to have a quick look. It’s a dramatic vision of divine intervention in the organisation of powers, political for God’s divinely-given one. In the first opening section (vv.1-8), four hybrid animals emerging out of the waters, coming before God and experiencing judgement. The first is a lion with eagle’s wings, the second a three-tusked bear, the third a leopard with wings and four heads and the fourth a terrifying, arrogant and particularly fearsome beast with ten horns and iron teeth. Following the appearance of the four beasts, the Ancient of Days appears and the judgement books are opened (vv.9-10). The fourth beast is destroyed (v.11). Then one “like a son of man” appears, coming into the presence of the Ancient of Days and is given an everlasting kingdom and authority over all dominions (i.e. the four beasts) (vv.12-14). The second half of the chapter (vv.15-28), following the vision, is taken up with Daniel asking for, as well as receiving, an explanation of what he had just seen. In the explanation we learn that the 4th beast (the most fearsome one) would be at war with the ‘holy ones’ and for a time it might even look like this beast has won (vv.23-27).

Political Power & Beasts from the Sea in Daniel 7

This is the first follow-up post to the "Is it the "End of Days"? Reading the Bible faithfully in the digital age (Part 1)."

Daniel 7: beastly powers and their rise and fall

So what is going on?

This is one of those bizarre scenes that is alien to many readers of the Bible. What is happening? What’s it all about? In short, this is about the power of God versus the political powers of the day. This is not about end-of-time speculation. Think of it more like an unveiling of hidden mysteries that help us see the world differently. Yes, it includes elements of future hope for Israel (and certainly there are many strands that are taken up and find significance in light of the Cross), but it also speaks to past events and all of it is really focused on shoring up strength in the present.

A few keys

Here are a few useful things to note:

- The four powers represent the empires of Babylon, Media, Persia and Greece (who is the fourth beast). [Notice the references to Greece in the chapters that follow.]

- The “little horn” that appears and has a face and speaks arrogantly refers to Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a Greek ruler who desecrated the temple as well as using it for its riches to fund his military campaigns.

- The son of man figure is not a messianic prophecy, but most probably a depiction of the angel Michael as guardian angel of Israel, receiving dominion from God. In other words, he embodies the God-given confidence that Israel will one day be free of Greek imperial rule. [Notice how the figure is going towards the Anicent of Days and the heavenly courtroom. He is not coming to earth.]

So what do we learn about the powers in Daniel 7?

1. Political empires aren’t directly God-appointed

Notice the four beasts all come from the Sea. In ancient Israel, the Sea was at the very least a symbol of chaos and evil for its unpredictability and inability to be tamed by human hand. There is also good reason to suggest it represents evil mythological powers that oppose God as well. (There’s a long tradition in the OT of the Sea being used similarly to its appearance in Ugaritic mythology as the chaos monster who opposes the storm-god Baal). That the four beasts come from the Sea and that they are not animals but monstrous beasts, all point to being out of the order of God’s creation. They are chaotic, they oppose God (at least to some extent), although some are worse than others, i.e. beasty number 4.

2. Political empires are God-permitted

In this little chapter, although the empires come from the Sea, that is not to say God does not permit them to exist and make allowance for them. Yes, when the Ancient of Days appears, the 4th beast is destroyed and the others have their dominion taken away, but they are allowed to exist for a time (see v.12). We later learn that even though the 4th beast is at war with God’s holy ones, his time isn’t up yet—he will be permitted to continue for “a time, two times and half a time” (v.25). God will act, even if the moment is not when we would want it. Time is important in God's economy—the appointed time for things to happen. As humans we are bound by chronological time (and the ageing that goes with that). In Daniel 7 and similar literature the “appointed time” is important. [See Habakkuk 1-2 for an example of how God uses Babylon as the means of God's judgement upon Israel, but not without limits, Babylon too will be held to account and have limits put on its dominion.] And when the dominion is taken away and given to the son of man figure, he will have authority over all of them (cf. v.14 and 27).

3. Some political empires are significantly worse than others:

Not all imperial powers are equal. Some are worse than others. The 4th beast, the Greek empire, was the one that perishes before the Ancient of Days and has its body handed over to be burned (v.11). Its life is not spared, as it was for the other three empires who simply had their power taken away but are allowed to live a little longer. Why this difference in treatment? Well, this beast is “different” from those who came before (v.7) with the emphasis on its arrogance (v.8, 11 and 20) and its intrinsically violent nature—it is terrifying and strong (v.7), it makes war with the holy ones and devours the earth (v.19, 23). Its “little horn” is similar and with its humanistic features reflects the whole: it will blaspheme God, wear out the holy ones and try to pervert their religion (v.8, 24-27).

[This "little horn" king tracks with what we know of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, whose appellation “Epiphanes” claimed that he was the revelation of the divine. He ransacked the temple to fuel his military campaigns as well as setting up a false altar in it and sacrificed a pig there. For more of Antiochus see 1-2 Maccabees and Josephus’ Antiquities.]

4. Political powers will be judged and will not last—for God’s kingdom will prevail

What is striking when you study these beasts up close, is that they never stand a chance against the Ancient of Days. This isn’t Darth Vader vs. Yoda. Or Voldemort vs. Dumbledore. It’s not an interaction of equals with a lengthy, drawn-out battle (as you would find in an action movie. For the record, Daniel 7 would make a terrible action film). For all the destruction the fourth beast wreaks, before the Ancient of Days it is utterly powerless. The other beasts may have had power, but they too are powerless when the Ancient of Days calls time and takes it away. And ultimately, although God’s people hearing the words of Daniel 7 are still facing the terror of the 4th beast and its little horn (i.e. the Greek empire and Antiochus IV), the promise is that this imperial power will come to an end and will be judged. And God’s kingdom—a kingdom that comes from heaven rather than one that comes up from the Sea—this kingdom will be forever.

This is how Daniel 7 is really about the present age of God’s people in the 2nd century. The future hope in Daniel (i.e. the end of the 4th beast and the arrival of the kingdom of God) gives strength to God’s people today, in light of their present sufferings and struggles. It gives them courage that God is still God, even when it looks like the gods of the Greeks have the upper hand—or even seemingly defeated the God of Israel. This peek behind the cosmic curtain gives a bigger picture that says the best is yet to come. This is not the end of the story: there is more to come.

Does any of it apply today?

So what do we take from it? Well, this is just one picture of political power in the Bible, so it's important to remember this in the context of the whole and not go wild. That said, it does seem to remind us to remember the differentiation between a divinely-wrought kingdom versus human ones. Political empires in Daniel 7 are from the Sea, God-accommodated (but not created), subject to punishment and finite. Some are significantly worse than others in their transgressions. Compare that with God's kingdom in Daniel 7: from heaven, God-given, eternal and will have authority over all other kingdoms. It may not be present yet in the way the reader might want, but it points us towards remembering that one day it will be so.

I wonder whether Daniel 7 paints a useful picture to remember in our speech about political powers. They have their purposes and reasons for their existence (God's accommodates, after all), but they are not divinely-ratified. They are not an intrinsic part of the original design for Creation. Whether we're talking king, president or prime minister, they are (in Daniel's vision) that which comes from below not above. So let's be careful to not confuse the two.

******

Cove photo by Pop & Zebra on Unsplash

Inset image: Public Domain, from the British Library's collections, 2013